The Obscure Case of Leonard Cohen

and

The Mysterious Mr. M.

by Bruce Pollock

After Dark, February 1977

As I hustled up Sixth Avenue toward the Algonquin Hotel for an interview

with Columbia recording artist Leonard Cohen, writer of such heavyweight

literary pop songs as "Suzanne," "Bird on a Wire," and "Dress Rehearsal Rag,"

I anticipated an epic conversation, a gargantuan verbal feast, an orgy of

philosophical anecdote and analogy. Cohen, after all, far from being merely

another songwriter, was a published poet when he was fifteen, is a novelist

twice over (Favorite Game, Beautiful Losers), and I was about to be

a published author myself. Cohen had read my book; I had read both of his.

We'd be two authors talking shop. Before the afternoon was through, I was

sure I'd have him begging me to send him one (if not all seven) of my unpublished

novels. Perhaps a correspondence would result --the famous Cohen-Pollock

letters, later to be collected in an expensive, coffee-table edition.

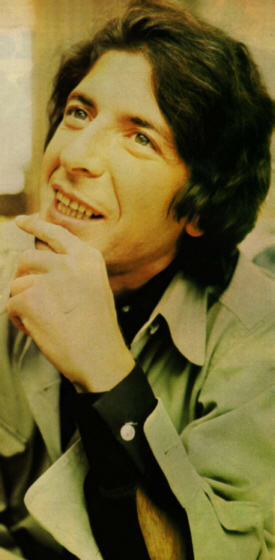

When I entered Cohen's room, I was rather surprised to find another interviewer

in the process of finishing up his visit. How were Cohen and I to achieve

any literary epiphanies with this eavesdropper, obviously a rock-and-roll

degenerate, sitting on the couch drinking wine? Cohen sat in a chair at a

table in the far corner, wearing the same gray pants and black shirt he'd

worn during his concert the night before.

"If you'd rather be alone, M---- will leave," Cohen said as I set up my tape

recorder on the table.

"He can stay," I said, then after a pregnant pause, "another five minutes."

That settled, I commenced questioning Cohen about his first novel. How did

he react to its publication and subsequent commercial failure? As he was

fashioning a response, I began preparing myself to tell him about my

first novel --still unpublished --my own expectations and fantasies. However,

before I could verbalize them, he spoke.

"My training as a writer was not calculated to inflame the appetites," he

said with ease. "In Montreal in the fifties, when I began to write, people

didn't have the notion of superstars. The same prizes weren't in the air

as there are today, so one had a kind of modest view of what a writing career

was."

I couldn't have put it better myself. M----, still on the couch, showed no

signs of leaving. Steadily swallowing wine, he ogled us with a slight smile

with which he seemed to be transmitting signals to Cohen. "I just hope this

doesn't get too boring for you," I told him. "I mean, for all I know, I may

be asking him the same questions you did." Of course, I knew that wouldn't

be the case. I'd be asking him insightful, prose-writer questions. Meaty

stuff.

M---- giggled. "Oh no," he slurred, "we didn't have that kind of interview.

We were on a totally different wavelength."

Rattled, I immediately quoted from an obscure article Cohen had written eight

years ago in an obscure publication called Books, about his first

performance onstage as a singer and the beauty of his utter failure. Totally

different wavelength, huh? I'd show the both of them wavelengths! In the

light of his career since then, would he still say it was better to fail

than succeed? I asked adroitly.

This was such an arcane reference that M---- was awed back into silence,

and Cohen himself was hard-pressed to recall it. However, when he did, I

could see he was impressed. His answer came in the form of an allegory.

"A man visits a master who's living in a very pitiful terrain and the man

says, 'How can you survive here?' The master says, 'If you think it's bad

now, you should see what it's like in summer.' 'What happens in summer?'

asks the man. The master says, 'In the summer I throw myself into a vat of

boiling oil.' 'Isn't it worse then?' says the man. 'No,' says the master,

'pain cannot reach you there.'"

"That's really the way things are," Cohen continued after acknowledging the

chuckles from M----. "If you throw yourself into a kind of effort, it's not

better or worse. Like a chameleon, you take the color of the experience if

it's intense enough, and the pain cannot reach you there."

"Performing is definitely the boiling oil. You can't really develop an

intellectual perspective on it --I mean, you're in it. You realize the next

moment could bring total humiliation --or you could actually be lifted up

into the emotion that began the song. But you're already in the boiling oil

by the time you've gotten that far."

At this point M---- burst in and asked Cohen if a character in Beautiful

Losers was a real person. "Composite," Cohen answered. Then, before I

could regain my balance, M---- recited an entire paragraph from page 143

of the book --to Cohen's obvious delight. I too had read the book but had

not thought to memorize it. Score one for M----. Retaliating, I brought up

a moment from his concert, when he delivered a beautifully worded monologue

about searching for the women who inspired "Sisters of Mercy." I asked him

if he was, like the true romantic he set himself up to be, haunted by the

past.

He seemed interested in the topic. "I think everybody is involved in a kind

of Count of Monte Christo feeling. You somehow want the past to be vindicated.

You want to evoke figures of the past. My own experience has been that almost

everything you want happens. I meet people out of the past all the time.

Not only that, I meet people that I wanted to create. It's like Nancy..."

Cohen went on, referring to one of his songs, caught up in the idea. "The

line is 'now you look around, you see her everywhere...' This is just my

own creation, but obviously there's a collective appetite for a certain kind

of individual; that individual's created and you feel you had a certain tiny

part in that creation."

Now that was a serious concept, something only two fiction writers could

really get to the bottom of. But just as I was about to sink my teeth into

it, M---- hurled himself once again into the flow. "Does that song have anything

to do with Marilyn Monroe?"

"No," said Cohen, "it was about a real Nancy."

By the time they'd finished discussing Marilyn Monroe, my momentum had been

lost. Although it hadn't been in my original game plan, I pulled a surprise

by asking Cohen about longevity in songwriters, why so few lasted past

adolescence.

"I think there are a number of things that bear on that," said Cohen, fielding

the hot shot and throwing me out by a good two feet. "You can burn yourself

out, for one. The late teens and twenties are generally the lyric phase of

a writer's career. If you achieve enough fame and women and money during

that period, you quit, because that's generally the motivation. I mean, I

didn't get enough money or women or fame for me to quit. I don't have enough

yet, so I've got to keep on playing." He laughed. "I know it's rather unbecoming

at forty to keep it all going, but I have to do it."

I couldn't decide if he was putting me on or not. While my own train of thought

stalled, M---- roared in on the express. "Why do you in your songs, refer

to yourself as ugly?" he asked.

Cohen smiled at him. "How do I look today?"

"You look handsome," said the now besotted M----, "energetic and alive."

"I need a haircut," parried Cohen.

"Maybe I will have some wine after all," I said, although no one had

offered me any.

M---- passed me the bottle while Cohen extemporized further on his looks.

"Actually, I've grown a lot better looking since I began calling myself ugly."

M---- accused him of self-hatred.

"Maybe it's self-hatred," Cohen allowed, "maybe it's bending over backwards

for accuracy."

"Cheese?" I said to no one in particular, "why of course, thank you."

"I mean, in the sixties when I was writing the songs that come out of that

experience," Cohen explained, "I saw really beautiful youths around. It's

all a relative thing. If you're at a bar mitzvah, you may look pretty good;

however, if you're with a bunch of lead guitarists at the Chelsea Hotel in

1966, and they're all beautiful tall blonde youths..."

"I don't think so," M---- protested. "I think a lot of them just look very

hairy. I think it's harder to look good at forty."

"Most of these lead guitarists don't make it to forty," I felt compelled

to insert. They both ignored me. I drained the bottle.

"I feel okay these days, you know. I'm making a living. I managed to get

away from my family. I've been through a war. I'm okay."

M---- suddenly turned to me. "Go on," he said, motioning me back to my interview.

"Hah?"

"A friend of mine said about poetry," Cohen told M----, "that the two things

necessary for a young poet are arrogance and inexperience."

M---- seemed to identify. "What about a prose-writer?" I cried in panic.

"Do you think it's the same thing, too?" However, M---- was already reciting

one of his poems to Cohen. Although I thought it a paltry work, Cohen seemed

to like it. I cursed myself for not having had the sense to bring along one,

if not all seven, of my unpublished novels for him to read. While M---- recited

another poem, I realized they were on the wavelength I had wanted to reach.

M---- was up there with Cohen, poet to poet, while I trailed a distant second,

the interviewer, straightman, fink.

Finally M---- got up to go to the john. Alone at last. Here was my big chance.

With one sweeping question I could re-establish myself as an equal in Cohen's

eyes. Instead I wound up asking him if he ever got letters from his fans

and how he responded.

"You've got to play it by ear," he said. "You can involve yourself totally

in the lives of your listeners, and it has got to be disaster. I mean, I

put my work out the very best I can. It comes out of my life. It's a very

large chunk of my life. I can understand if it becomes important in another

life. But whether you involve yourself personally in these other lives is

another matter."

"I'm not talking about somebody who has a fantasy of a singer. These are

people who really relate to your own experience and vice versa. Now maybe

they're living some kind of milieu where they don't have people to relate

to. You set yourself up as a kind of kin to these people and they see it

and it's true. That's the fantastic thing about it. You meet them and immediately

you see they are people who have your own experience. So over the years I

have somehow fallen into some lives that my songs have led me into, and some

of these lives have ended --rather violently, rather sadly..."

When M---- emerged from the john, Cohen told us that he must leave for a

recording session. M---- asked if he could tag along, but Cohen said no,

which pleased me no end. I suggested to M---- that if he were going downtown,

I'd walk him part of the way. He said okay.

There's really a one-to-one relationship between Cohen and his songs, his

books, of that much I was sure. Here were M---- and I filling up yet another

chapter --two seekers, neophytes, in a foot race to the door of the master.

At least we'd be leaving together. Not only was I salvaging a tie out of

the day's proceedings, but I felt I was rescuing Cohen from a potentially

maudlin evening with M----. In the next life Cohen might thank me.

However, as we neared the elevators, as if he'd forgotten something, M----

wheeled around and headed back to Cohen's room, advising me to go on without

him. What a move! I stood flatfooted in the hallway with no other choice

but to leave, which I did. Score another one for M----.

|

![[PREV PAGE]](but-prev.gif)

![[NEXT PAGE]](but-next.gif)

![[INDEX PAGE]](but-ndx.gif)

![[SUB INDEX PAGE]](but-subi.gif)

![[PREV PAGE]](but-prev.gif)

![[NEXT PAGE]](but-next.gif)

![[INDEX PAGE]](but-ndx.gif)

![[SUB INDEX PAGE]](but-subi.gif)